When I spoke to [Charles K. Feldman]…I said he should make a straight Bond, find a new actor, and have one shot and he’d make a lot of money. Which he could have, by copying the book, because the book was a good book. And they screwed it up by listening to all the so-called geniuses—the directors, the writers, the whole complex. – Albert R. Broccoli

But the most way-out spy film of all was Casino Royale (1967), a bizarre concoction that has virtually nothing to do with the first (and arguably the best) of Ian Fleming ‘s James Bond novels. 'Casino Royale' only made me laugh twice during its TWO-AND-A-HALF-HOUR RUNTIME. 'The Silencers' was an hour shorter, and infinitely funnier. In total, this is one of the worst films I've ever.

Casino Royale (1967) review. Director: John Huston, Ken Hughes, Val Guest, Joseph McGrath. Starring: David Niven, Peter Sellers, Ursula Andress, Joanna Pettet, Orson. Burt Bacharach appropriately comes up with a rambunctious soundtrack for the 1967 James Bond spoof, Casino Royale. Things get underway with Herb Alpert and the Tijuana Brass' performance of the fast-paced main title, which features the usual Bacharach mix of pop phrasing and complex arrangements; this theme is subsequently augmented with a lush string.

I think the film stinks, as does my role. There is no involvement or story or importance to any of it. It is silly like an old [Milton] Berle sketch as opposed to a fine Nichols and May sketch. There is no seriousness or maturity of approach. It is unfunny burlesque. – Woody Allen

Casino Royale is either going to be a classic bit of fun or the biggest fuck-up since the Flood. I think perhaps the latter. – David Niven

If James Bond was at the forefront of the Swinging Sixties as the decade achieved liftoff, then perhaps it’s fitting that Casino Royale heralds the era’s crash landing. Released just prior to the Summer of Love, just before societal and political tumult dragged the world into the seventies, the movie is the ultimate sixties party: excessive and uncontrolled, stoned out and hung over, deliriously exhausted.

Casino Royale 1967 Movie Cast

How this gargantuan project came to be merits an entire book by itself, but the story starts and ends with flamboyant talent agent-turned-producer Charles K. Feldman, who acquired the rights to Ian Fleming’s first Bond novel, Casino Royale, in 1960. Unlike Kevin McClory, the renegade producer who partnered with official Bond producers Albert Broccoli and Harry Saltzman on Thunderball, Feldman was no small-time operator, as demonstrated by his credits: Red River, A Streetcar Named Desire and The Seven-year Itch, to name a few. As Broccoli and Saltzman’s Bond movies hit box-office pay dirt, Feldman cashed in his Casino chip and lobbied them hard to co-produce the property with him. When he was rebuffed, he took on the task by himself.

Initially toying with the idea of creating a straightforward thriller, Feldman commissioned a script by Hollywood legend Ben Hecht, the author of classics such as Hitchcock’s Notorious. (In what was a portent of things to come, Hecht died within two days of turning in his draft, which mostly went unused.) Feldman even attempted to lure Sean Connery on board to play Bond, but when Connery demanded a then-unheard-of $1 million salary, Feldman settled for the next best option: David Niven, who had once been considered for the official Bond. Feldman also did a 180 on the film’s tone, taking inspiration from his most recent success: What’s New Pussycat?, a rollicking ramshackle mess of a comedy both silly and sweet. Importing two of the comedic stars from the film, Peter Sellers and Woody Allen, along with former Bond girl Ursula Andress, Feldman spared no expense, assembling the hands-down starriest cast to ever appear in a Bond flick, and throwing $6 million into the production.

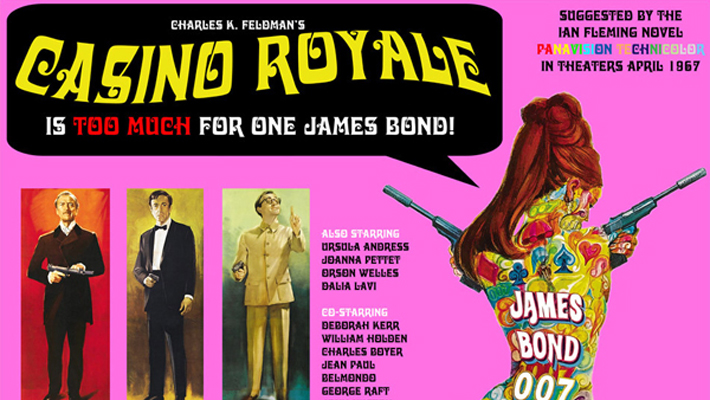

By the end of filming, the budget had ballooned to $12 million (“Little Cleopatra,” the tabloids dubbed the production, referencing the massively expensive Elizabeth Taylor film), and shooting delays had run rampant. Scenes were rewritten on the fly, as actors floated in and out of the production. The mercurial Sellers dropped out of the film altogether before a suitable ending had been devised for him, forcing a last-minute edit that had him (unconvincingly) getting shot. An absurd number of creatives ventured into the fray: directors Val Guest, Ken Hughes, John Huston, Joseph McGrath and Robert Parrish, and screenplay writers Wolf Mankowitz, John Law, and Michael Sayers (it’s rumored that Woody Allen, Joseph Heller, Terry Southern and Billy Wilder also contributed). With so many cooks in the kitchen, it’s no surprise the film’s plot (which all but abandons the novel) goes similarly overboard, with over half a dozen actors either portraying or posing as James Bond. Posters proclaimed: “Casino Royale is too much … for one James Bond!”

Yet the start of Feldman’s Casino Royale, bizarre as it is, seems to promise an actual point and approach. We are informed that Sir James Bond (Niven) has been in seclusion for years, while other agents have inherited his name and double-oh number. Surrounded by a gaggle of ornery lions (“I did not come here to be devoured by symbols of monarchy!” grouses a KGB visitor as “Born Free” triumphantly blares on the soundtrack), the retired agent is content to plink Debussy suites on his grand piano and cultivate roses. When M (a garrulous John Huston, who also directed this segment) comes calling, begging him to return to service, Bond will have none of it: “In my day, spying was an alternative to war, and the spy was the member of a select and immaculate priesthood,” he explains. “Vocationally devoted, sublimely disinterested. Hardly a description of that sexual acrobat who leaves a trail of beautiful dead women like blown roses behind him…that bounder who you gave my name and number.” In one satiric swoop, the filmmakers thus suggest that the Bond of the official series is a perversion, a downgraded copy of a knightly hero from a more chivalric age. Instead of “Aston Martins with lethal accessories,” “joke shop” gadgets and erotic escapades, this Bond is all about virtue and modesty. When he learns that other British agents have met unsavory ends (“stabbed to death in a ladies’ sauna bath…burned in a blazing bordello…garroted in a geisha house”), he can only tsk-tsk: “It’s depressing that the words ‘secret agent’ have become synonymous with ‘sex maniac.’”

It’s an intriguingly original take on the 007 mythos,and suggests there’s comic mileage to be had in plopping Niven’s chivalrousGalahad into the middle of the over-sexed sixties. The film’s next passagefollows up on this idea: After M is accidentally blown up, Bond brings theremains (mainly his toupee—“It can only be regarded as a hair-loom”) to hisboss’s ancestral Scottish estate, only to find it occupied by double agent Mimi(Deborah Kerr) and a gaggle of scantily-clad lovelies, all of whom are intent onsoiling his honor. “Doodle me, Jimmy,” Mimi sighs in heavy Scottish brogue. “Aquaint custom, but one more honored in the breech than in the observance,” Bondreplies. In retaliation, he’s subjected to a bizarre cannonball-throwingcompetition, followed by a drone missile ambush during a grouse hunt. But neverfear: Sir James’s rectitude is so overwhelming that Mimi is soon smitten, tothe point that she forsakes worldly spy games in favor of life in a convent.

If that preceding synopsis (which covers the first quarter of the film) isn’t bewildering enough, the story only gets more mystifying. Taking over for M, Sir James faces a new evil in the form of SMERSH (aka “The Authority” and “International Mothers Help”). To confuse the enemy (as well as the audience), he makes the radical decision to rename every British agent in the field as “James Bond 007”. Ms. Moneypenny’s daughter (Barbara Bouchet, the sultriest of all Moneypennys) is tasked with recruiting new, viable James Bonds via French-kissing them. Meanwhile, Sir James hires mercenary spy Vesper Lynd (Ursula Andress) to recruit card sharp Evelyn Tremble (Peter Sellers) to face the villainous Le Chiffre (Orson Welles) at the baccarat tables, for reasons that are only vaguely explained. Speaking of matters beyond explanation, it turns out that Sir James sired an illegitimate daughter with the infamous spy Mata Hari, and he quickly convinces his now-bodacious offspring (Joanna Pettet) to infiltrate International Mothers Help Headquarters in Berlin. All roads finally converge at the Casino Royale, which also serves as the secret base for the true mastermind behind SMERSH: Dr. Noah, better known as Jimmy Bond (Woody Allen), Sir James’s resentful nephew. His diabolical plan? Unleash bacteriological warfare which will make every woman in the world beautiful and kill every man taller than he is.

As a summary, it all sounds just parodic enough, if not necessarily coherent. Certainly anyone with even a glancing knowledge of Mike Meyers’ Austin Powers series, which steals its groovy vibe from Casino Royale, will find much to recognize. But no summary can accurately describe the film’s psychedelic lunacy, as it hops through moods and genres as often as Ursula Andress changes costumes. Mata Bond is introduced via a kitschy musical production number that would slide nicely into The King and I, while her later infiltration of Berlin’s SMERSH headquarters is jam-packed with Dutch angles and expressionistic sets ripped from The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. The verbal humor alternates between innuendo heavy enough to sink a battleship and non-sequiturs that tie themselves into intellectual knots (“Who is Le Chiffre?” “Nobody knows, not even Le Chiffre”), while the slapstick barely qualifies as such. Strangely enough, these flailing attempts to wed high-minded wordplay with low comedy anticipate the emergence of Monty Python and their unique brand of brainy absurdity half a decade later (only without half of Python’s wit or discipline). Other moments are simply bewildering, as when Bond, attempting to escape a villain’s hideout, runs into Frankenstein’s monster, who helpfully provides him with directions.

In its more lucid passages, Casino Royale throws knowing winks at the Bond mythos. Tremble’s visit with Q branch features scuba divers with bows and arrows, dwarves with binoculars, and gadget-laden vests emblazoned with the Union Jack, available in “chocolate, oyster or clerical grey.” “You really do start everything at Harrod’s, don’t you?” Tremble muses. (The ultimate irony, of course, is that Q scenes in official Bond entries would eventually descend to a similar level of comedy.) As in the official series, duplicitous enemy agents with provocative names must be contended with, such as the seductive Miss Goodthighs (Jacqueline Bisset), while prospective Bond wanna-bes like Cooper (Terence Cooper) must prove themselves resistant to the ample charms of a bevy of women, including one who dresses herself up as Dr. No’s Honey Ryder. At times, the very act of espionage is reduced to a joke: agents are rendered as idiotic buffoons, mired in an indecipherable alphabet soup of agency acronyms. A spy instructor (played by the marvelously arch Anna Quayle) is a mass of nonsensical ravings, secure in her own superiority: “You’re insane, my child, quite insane,” she purrs at Pettet. In another passage, a SMERSH agent (Vladek Sheybal) auctions off incriminating sexy photos to blundering military officials from all around the world, the scene approaching Dr. Strangelove levels of satire. (“A wagon load of vodka!” bids a soused Russian official. “Seventy million tons of rice!” counters a belligerent Chinese general.)

Watch Casino Royale 1967

But this meta-commentary makes little impact when the movie offers nothing solid to hold onto—and that includes the characters. Niven begins the film as a shy, stammering hermit before jettisoning his stammer and timidity in short order (“I haven’t got time for that now,” is his only explanation). Sellers mostly plays it straight as the mild-mannered, out-of-his-depth Tremble, but can’t resist breaking into jokey Indian and Chinese accents at the gaming tables, or breaking character completely to adopt the costume, brogue and bravado of race-car legend Jackie Stewart just prior to a climactic car chase (as is par for the course in this movie, the entire chase happens off-screen—in the next shot, Sellers has already been captured by the enemy). Orson Welles’ Le Chiffre approximates the menace of a Bond villain, but what are we to make of his predilection for wowing casino crowds with extravagant Vegas-style magic tricks? (Welles was heavy into magic at the time, and lobbied to have his act filmed in the movie.) Like Vesper in Fleming’s Casino Royale, Andress’s Vesper is revealed to be a traitor; unlike Fleming’s Vesper, there’s no reasoning or consequences behind her heel turn. Other stars like Peter O’Toole, George Raft, Jean-Paul Belmondo and William Holden are literal walk-ons, shuffling into the frame for a half-hearted stab at humor, then disappearing. Indiscriminately throwing these cameos and incongruous gags at the audience, as if points are being handed out for quantity rather than quality, Casino Royale is a story without a purpose, a joke without a punchline.

Which isn’t to say that the movie is unwatchable. When it’s not pushing too hard to assault us with an over-frenetic setpiece, the film has an almost Zen-like serenity amidst all the hijinks. Cinematographer Nicholas Roeg bathes even the most ridiculous moments in a burnished glow, while Burt Bacharach’s fleet, stately pop dream of a soundtrack keeps matters light as air, even as the film sinks into chaos. At its best, Casino Royale takes its time to luxuriate in the accoutrements of Bond’s world: the space-age furnishings, the impossibly sensuous women, the sheer giddiness of the swinger’s life. One can almost imagine the film as a libidinous fever dream of Fleming’s Bond, in which men are silly, women are silly and sexy, and spying is ultimately less important than shagging. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the film’s best sequence, in which Vesper seduces Tremble in her apartment, the scene underscored by Dusty Springfield’s classic “The Look of Love,” filmed in gauzy slow motion. In such a setting, even the self-possessed Sellers can’t resist the languor of it all. “England expects every man to do his duty,” smiles a radiant Andress; Sellers’ almost abashed reaction is the most human moment in the film. Best of all is Woody Allen, who somehow steals the film despite getting only 10 minutes of total screen time. True, he’s deploying his usual neurotic shtick, but compared to the unfocused disarray of the rest of the movie, his true-to-form humor is like a cool refreshing breeze. The funniest visual gag also belongs to him: escaping a South American firing squad, he leaps over a wall to safety—only to find himself caught in the middle of another execution by firing squad.

Casino Royale’s finish redefines “everything but the kitchen sink,” as the filmmakers throw their hands up, giving in to their most indulgent impulses. Inflating the standard “Bond joins up with allies to fight enemy army” finale to ludicrous levels, the final conflagration is crammed with everything one can conjure up, and plenty that no normal human with sound mind would think of: Native American warriors jumping out of airplanes yelling “Geronimo!”, cowboys and keystone cops, a levitating roulette wheel spitting out laughing gas, apes with wigs, soap bubbles galore, dogs and seals wearing collars labeled 007. A nuclear explosion serves as the final punchline, as all plot threads and characters are literally vaporized. Some might detect some symbolism in this—how else to end a treatise on James Bond and sixties pop culture spinning out of control but with one very big bang? Others will argue the film was a comedic springboard, presaging the branching paths of film comedy over the next decade: increasingly baroque, surreal burlesques (many of them starring Sellers), out-and-out spoofs of treasured genres (a sub-genre eventually mastered by Mel Brooks), and Woody Allen’s own nebbishy fantasias (Take the Money and Run, Bananas). Some critics such as Robert von Dassanowsky have championed the film as a postmodern cult classic, a stimulating collision of pop art, cheeky deconstruction, and effervescent mod excess. Still others opine that Casino Royale is exactly what it appears to be: one spectacular mess of a movie.

Critics at the time agreed with the latter view. Stating the obvious, Roger Ebert wrote, “This is possibly the most indulgent film ever made,” while Variety panned the film as “a conglomeration of frenzied situations, ‘in’ gags and special effects, lacking discipline and cohesion.” The New York Times’ Bosley Crowther came the closest to pegging the vibe of the film: “more of the talent agent than the secret agent.” Although the film made out fine at the box office when it was released in spring 1967, eventually earning $42 million, the experience had been a rough one for Feldman—it was the last film he produced before succumbing to pancreatic cancer in 1968. Reportedly he even told Connery that paying him the $1 million to do the movie would have saved him a whole lot of heartache.

Despite (or perhaps because of) its singular status as a perplexing oddity in the Bond canon, Casino Royale still haunts Bond movies to this day. Both a monument to overindulgence and a perfect time capsule of the era, the film serves as a warning of what can happen when a big-budget movie jumps the rails—but it was also a harbinger of things to come. The concept of Bond had proven pliable and profitable, even when bent all out of shape, which had to be of some comfort for Broccoli and Saltzman, who were approaching an inflection point of their own: the threat of Sean Connery leaving the role. ■